Photos To Remember You By

Visiting him (2021)

When I take photos, I only really think about them later on. I have always found it interesting to look for patterns and messages in my work. What are these images about my father telling me? After observing and photographing him for the past few years more intentionally, it is all starting to become clearer. I see now that being a strong man is about being the most selfless version of yourself. For my dad, this meant not processing his brother’s death overtly and instead, being there for others. Perhaps him being strong for the people around him has been his way of processing this loss after all. This type of silence, unfortunately, is often confused with the protection of one’s ego. I don’t see that in my father. I don’t think I ever will.

Pride, tradition, masculinity; all these notions just get in the way. For a long time, I could not properly put into words what this death had meant to me. It felt unfair and it made me angry. It was sudden, tragic and in more ways than one, unnatural. The people who surrounded me, those who mattered most, were launched into an unexpected and intense grieving process too. There was a huge elephant in the room, and I soon found myself reflecting on why we decide to suppress our emotions when dealing with situations like these. I quickly realized that death isn’t really something you openly discuss in an Italian family. It isn’t something that we allow ourselves to quickly move on from either.

Alone time (2020)

Family supper (2016)

Long drive (2020)

Shoe shine (2020)

In 2015, when I decided to take up photography, my father gifted me the Pentax Spotmatic F he had received from his parents in 1976. I had just discovered the work of Gordon Parks in an elective photography class and was inspired by the look of Parks’ black and white images. I subsequently began shooting black and white film because I felt pushed to document just about anything that caught my eye. I was, of course, unconsciously finding myself as an artist.

Picking up a camera revolved around a simple idea; I wanted to create family photos I would be happy with. My uncle had just passed away after a year-long battle with cancer and I had promised myself that I would, in the future, always have photos to remember my family by. I have since been especially drawn to photographing my father and his parents. The loss of this man, son, brother, and uncle was hard for all involved. I realized that the people around me were telling me something, without speaking. I hoped I could capture and document whatever it was that I saw, to help me understand and process this loss.

Cherished baptism chain (2020)

Setting up the patio (2019)

Through it all, I also wondered what was going through my father’s mind. I began to notice this change following my uncle’s diagnosis. My father is a man whose private and resilient nature shattered as he was told news of his brother on the phone, one afternoon. He broke down, crying for the first time in front of me, shouting on our kitchen floor. After countless visits between his brother’s place and the hospital in those last few months, dad would eventually lose one of the only people who truly knew him. All the things we would normally do together started to feel different, and most times, forced. With this loss, a bond that represented years of memories was gone too. Would he ever address his grief?

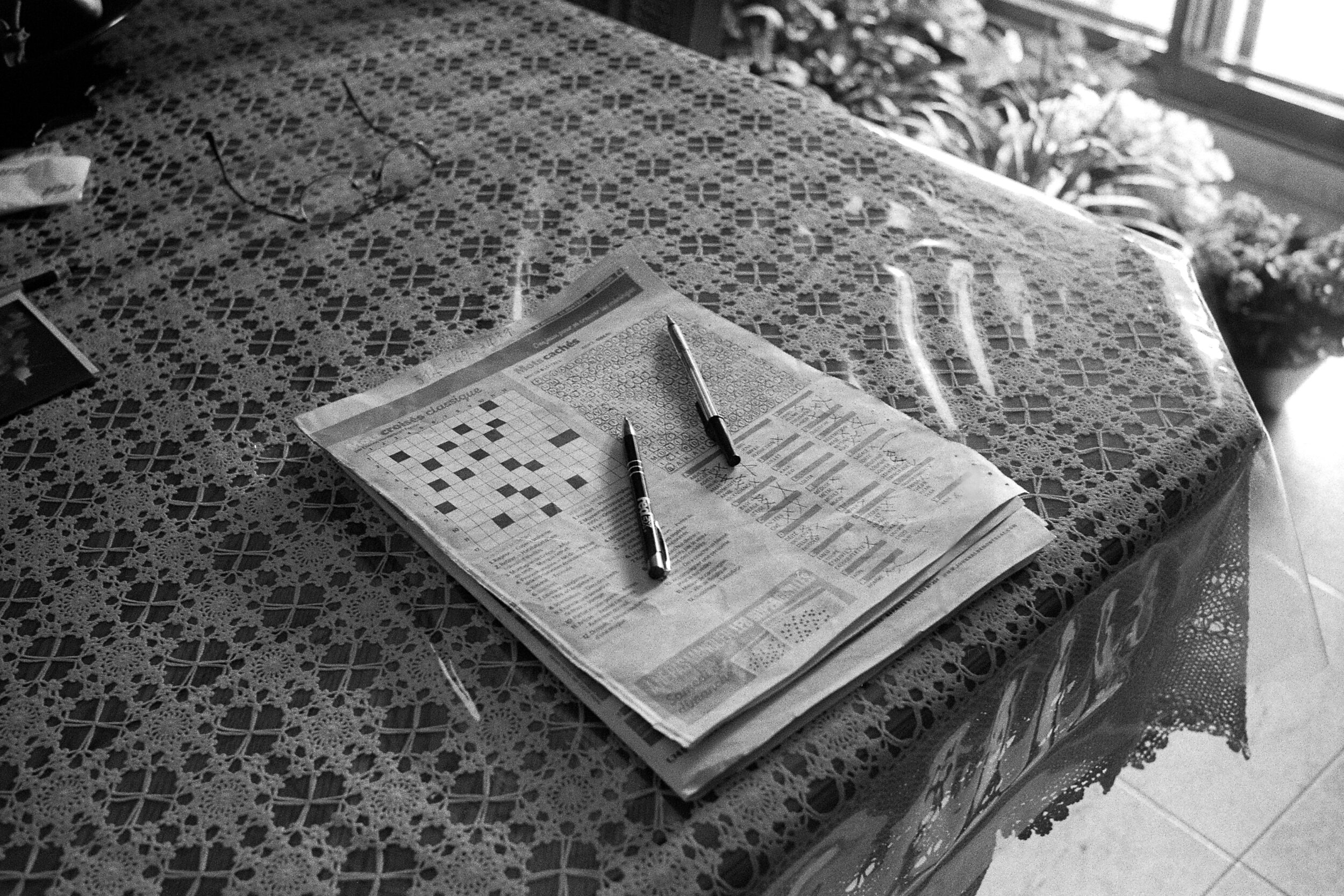

When you lose somebody, everything reminds you of them, you start to notice triggers. In my uncle’s case, small things like the smell of a cigar, a Fedex truck making a stop or the football game playing in the background made us all feel something. In fact, it still does, or maybe we naturally just cling onto the memory, to escape the reality of it all. Through all the questions you ask yourself, you begin to notice that the world, for better or for worse, is indifferent and that the traditions and routines you thought were taken away from you are merely transformed, not broken or axed.

Nosebleed (2021)

Mowing the lawn (2021)

By default, my father had been forced to carry a burden for everybody else in the family. It’s hard to properly address how you feel when you’re the only child that two distraught parents could turn to. You still need to be a husband and father. I quickly understood that for him, being the stoic head of the family was not a matter of choice, but rather, a matter of necessity. Life had to go on, even with this weight on his shoulders, and it was as though he understood this more than anyone. Still, I would often catch my dad thinking about his brother. A pause or a stare from him was telling now.

And so, for a few years, our new routine consisted of visiting the grandparents as often as we could and calling them daily. We became the support that they so desperately needed. As a result, these visits became nights gathered around the kitchen table with stories about this man who was taken too soon. It was in this period of readjustment, if you can call it that, that I noticed the positives we can take away from death. I began to let go of certain things. In an odd way, I began to view life through a different lens. I cherished my family even more. Simpler moments brought me more joy. Through this reductionism, my dad was still a point of reference for me. I became more understanding of what it meant to “be a man” simply by being around him through this time.

Edited by Antonio Mastrangelo

Purchase the print version of this photo essay here.

Prosciutto division (2020)

Painting the bedroom (2021)

His brother's shirts (2021)

Nonno's crossword and Fedex pen (2021)